It’s a Great Time to Own a Warehouse | September 2017

September 5, 2017

Supply chain innovation, e-commerce, and measured new supply have led to the best operating environment for industrial REITs that we can remember. However, investor demand has also surged. Industrial real estate is trading at record-high cash flow multiples in the public and private markets. For the first time in our memory, the best coastal warehouses are selling for higher multiples than many trophy Manhattan office towers, West Los Angeles street retail properties, and downtown San Francisco apartments.

We believe that investors are right to assume that industrial REITs will continue to grow cash flow per share faster than many other REIT sectors. However, we do not believe industrial REITs can outgrow other sectors forever. Historically, big-box (loosely defined as warehouses over 500,000 square feet) industrial has been prone to overbuilding, particularly in lower barrier submarkets, which has dampened long-term rent growth. In fact, aside from a few markets, the industrial sector has generated lower long-term rent growth than most other sectors, including apartments, offices, malls, and strip centers. Even if industrial’s long-term growth profile has improved, we do not believe the market is adequately pricing in the risk of a reversion to historical growth trends.

We believe many investors do not adequately differentiate between the types of industrial warehouse REITs, which has created mispricing within the sector. In particular, stock price performance for industrial REITs has been indifferent to portfolio quality and the above-mentioned risks. The growth of e-commerce and low interest rates have driven up the values of all industrial real estate, regardless of long-term growth potential and obsolescence risk.

While the entire sector may continue to outperform for some time, we believe investors can achieve the best risk-adjusted returns by focusing on industrial REITs that invest in ‘last mile’ warehouse space. These warehouses have the lowest supply risk and should benefit the most from retailers moving their supply chains toward their end consumer, which will allow them to create value and grow cash flow per share faster than their peers.

Not All Industrial Real Estate Is Equal

There are three types of industrial real estate: flex space, manufacturing property, and warehouse. Flex space is a hybrid between single-story office and warehouse space. It can house most ‘light’ industrial tenants but is more often used as a showroom, research & development facility, or back-office. Manufacturing properties are where raw goods are processed and most finished goods are made. Examples include factories, refineries, and assembly plants.

Warehouses are between flex and manufacturing, both with respect to their appearance and their place on the supply chain. After companies produce or process goods at manufacturing properties, they are sent to warehouses to be either stored or immediately distributed out to other warehouses, retail stores, or the end consumer. This publication focuses on warehouses because they are the primary assets owned by industrial REITs.

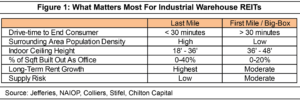

In our view, the most important distinction in the warehouse space is between last mile and ‘first mile/big-box’ warehouses (see Figure 1). The last mile/first mile distinction does not refer to literal units of distance; instead, it refers to parts of the supply chain. Logistics professionals define the last mile as everything that happens within a 30 minute drive of a finished good’s final destination, assuming typical traffic. The final destination is most often a retail store or the home of the end consumer. The first mile, by contrast, is everything that is not last mile. While the last mile represents a small percentage of the total distance a product has traveled, it usually comprises a large percentage of the total cost and time required for shipping.

We estimate 70% of leased industrial warehouses are first mile/big-box warehouses. These properties exceed 500,000 sqft and receive entire trailer/container-loads of goods from full truckload carriers such as Swift Transportation (NYSE: SWFT). They have many dock-level doors to cut down on the time needed to unload and load these trucks, high ceilings for racked storage, access to heavy power, and redundant fiber optic cables through which they run sophisticated inventory management systems. They are located far from urban centers but strategically between manufacturing properties and the end customer markets that they serve, usually close to interstate highways. Because they are so remote and there are relatively few barriers to their construction, existing big-box warehouses typically must compete with more new supply as a percentage of in-place inventory than last mile warehouses, a pattern which is compounded by the tendency of developers to build more large warehouses than small warehouses.

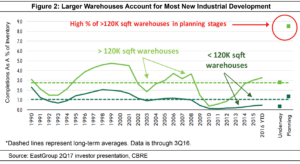

This is shown in Figure 2, which compares historical completions, ‘underway’ construction, and ‘in planning’ warehouse supply as a percent of existing inventory. In the chart, the solid and dashed light green lines represent the trend and historical average for properties larger than 120,000 sqft, respectively. The solid and dashed dark green lines represent the trend and historical average for properties smaller than 120,000 sqft. While these do not completely overlap with our last mile and big-box categories, the larger category is primarily big-box warehouses, while the smaller category has no big-box exposure.

Last mile warehouses receive smaller loads from carriers such as FedEx (NYSE: FDX). They are almost always smaller than 500,000 sqft, and typically smaller than 200,000 sqft. They tend to have fewer dock-level doors, lower ceilings, and less power/fiber infrastructure than big-box warehouses, but they have historically averaged higher rent growth because they have to compete with much less new supply. They tend to be older than big-box warehouses, but, even when they are the same age, they usually require landlords to spend more on capital expenditures (or ‘capex’), tenant improvements, and leasing commissions than first mile warehouses, as they have shorter leases and bigger office build-outs.

Drivers of Industrial REIT Outperformance

In our view, the three main factors contributing to industrial REITs’ recent outperformance are modern supply chain management, e-commerce, and measured new supply.

The field of supply chain management is largely responsible for getting companies to think about warehouses as a potential source of competitive advantage, as opposed to the historical approach of viewing them as cost centers which could only reduce company profits. This approach was radical when Sam Walton pioneered it at Wal-Mart (NYSE: WMT), but today it is the dominant approach of large retailers moving toward omnichannel, such as Amazon (NASDAQ: AMZN). Before Walton and AMZN founder Jeff Bezos, warehouse divisions used to balk at paying up for high-tech infrastructure or prime urban locations, but now they know that these costs can be more than offset by higher revenues.

Supply chain management was also instrumental in making possible the second driver of industrial REIT outperformance, the rise of e-commerce. Between 2005 and 2016, e-commerce retail sales grew by 16% annually in the US, much faster than the 2% annual growth in brick-and-mortar retail sales, using adjusted data from the US Census. It is true that e-commerce market share is still small, at 6% of total retail sales today versus 2% in 2005. However, this misses its true impact on real estate. Each dollar of e-commerce sales requires three times as much warehouse sqft as brick-and-mortar sales, and none of the retail sqft.

As a result, most experts believe e-commerce’s 6% share of retail is responsible for 25-40% of new warehouse leases. Jefferies, an investment research firm, estimates that Amazon alone was responsible for 9% of incremental US warehouse demand in 2016, and projects that number to rise to 11% in 2017.

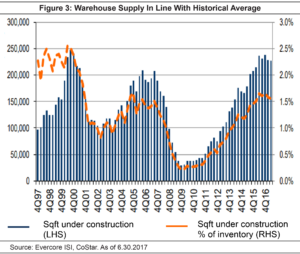

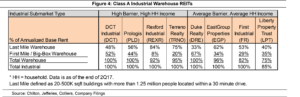

Finally, warehouses have benefited from measured levels of new construction. As shown in Figure 3, supply under construction is in-line with where it was from 2004-2007 but significantly below where it was in 1998-2000, the last time supply truly got out of hand. Most industrial REIT investors and lenders that we talk to believe the primary causes of this are (i) Basel III’s requirements that banks increase their required reserves for non-residential construction loans, (ii) a Dodd-Frank rule requiring lenders to keep some of each commercial mortgage-backed security that they issue on their balance sheet, and (iii) better market research on future supply. We are hopeful that these forces will keep total industrial supply from reaching 1998-2000 levels for several years. However, supply should impact the submarket types differently (see Figure 4).

The Industrial REIT Opportunity

With retailers attempting to compete with Amazon’s “Prime Now” same-day delivery service, e-commerce warehouse demand is increasingly shifting toward urban last mile warehouses. Most supply chain experts believe this is the only way that retailers can make same-day delivery profitable. For this reason, as well as the last mile’s superior long-term economics, we are focused on REITs that specialize in smaller, last mile warehouses in high income submarkets. Our favorite names in this space are Rexford Industrial Realty (NYSE: REXR) and EastGroup Properties (NYSE: EGP).

REXR, an owner of 16.2 million sqft as of June 30, invests in last mile properties in the highest barrier-to-entry submarkets in Los Angeles, Orange County, and San Diego. Its portfolio is a tiny fraction of the Southern California industrial market, which is the largest industrial market in the country, and its executives are local sharpshooters that have access to off-market transactions that are not available to other companies.

SoCal is the home of America’s two biggest ports and the gateway to Asia, boasting a market share of 38% of US container imports in 2016 (New York/Newark was next at 15.1%). Los Angeles in particular has some of the most restrictive zoning and lowest levels of new industrial supply of any large American city, which has resulted in some of the highest rents and lowest vacancy rates in the country.

As Figure 4 shows, REXR has more exposure to last mile warehouse space than any other REIT. Although REXR trades at a premium to the private market value of its properties, we believe the stability provided by irreplaceable locations in America’s best industrial market and management’s deep roots in the area will allow the company to grow value per share faster than most of its peers. In addition, with most of its submarkets expected to experience flat or declining industrial inventory over the next five years, we believe REXR’s cash flow growth and value creation carry much less risk than that of its larger and more diversified peers.

EastGroup Properties (NYSE: EGP), which owns 36.8 million sqft in the ‘smile’ of the country (California to Texas to North Carolina) as of June 30, boasts the third highest exposure to last mile space according to Jefferies. EGP has one of the best track records across all REIT sectors of producing consistent total returns for shareholders by creating value through development, which it prefers to do via multi-tenant industrial parks. Internally developed properties account for 17 million sqft or 46% of its total portfolio sqft as of June 30, which we believe to be among the highest of all REITs.

With 14% of its rent coming from Houston, EGP has demonstrated the quality of its locations in a difficult environment with occupancy rates only dropping 6% from the high-water mark of 98% in 2013 to 92% as of June 30, 2017, despite the decline of Houston’s oil and gas industry. Furthermore, it has reduced its Houston exposure from 20% of rent in 4Q15 to 14% today through dispositions including a park under contract to be sold in Q3, and has suspended new development until the market improves. Our analysis suggests that EGP should be able to witness a return to 95% occupancy by late 2018 in Houston. While other industrial REITs may be experiencing their cyclical peak for organic growth, EGP should be in a re-acceleration phase as Houston recovers.

Risks at Older First Mile Warehouses

Most of the warehouses owned by the REITs were built after 1990, and reflect many of the design changes that had previously facilitated just-in-time production at modern manufacturing buildings. We are less positive about big-box warehouses built before this period. These older assets are at a much higher risk of becoming obsolete, as it is often cheaper to build a new modern warehouse than it is to retrofit an old one. As a result, some of these assets could experience rent declines as their tenants increasingly move to more modern properties.

We are also concerned about the long-term future of big-box warehouses built in markets with low-barriers-to-entry, low population growth, and low household incomes. Owners of these properties will have a harder time raising rents than their peers, who benefit from less supply and better demographic trends. E-commerce companies will likely become more efficient users of industrial space over time, and these properties may be disproportionately affected when they do.

While big-box industrial REITs should continue to create value via development and grow cash flow through annual rent bumps, we believe the market is pricing in a much more favorable scenario. In contrast, we believe last mile warehouses will benefit from the shift of e-commerce demand growing closer to the end consumer while experiencing limited construction, which will create an environment of sustained rent growth and potential for consistent value creation through redevelopment.

Headlines of e-commerce market share growth and the decline of the mall (albeit class B and below) should buoy sentiment for all industrial REITs in the short term. However, as all industrial real estate was not created equal, there are some companies and properties that will fare better than others over the long term. We believe our industrial holdings will participate in the e-commerce wave and evolution of logistics, while also demonstrating lower risk to oversupply and cyclical demand thanks to high quality locations that cannot be duplicated by their peers.

Parker Rhea, prhea@chiltonreit.com, (713) 243-3211

Matthew R. Werner, CFA, mwerner@chiltonreit.com, (713) 243-3234

Bruce G. Garrison, CFA, bgarrison@chiltonreit.com, (713) 243-3233

Blane T. Cheatham, bcheatham@chiltonreit.com, (713) 243-3266

RMS: 1975 (8.31.2017) vs. 346 (3.6.2009) and 1330 (2.7.2007)

Previous editions of the Chilton Capital REIT Outlook are available at www.chiltonreit.com/reit-outlook.html.

An investment cannot be made directly in an index. The funds consist of securities which vary significantly from those in the benchmark indexes listed above and performance calculation methods may not be entirely comparable. Accordingly, comparing results shown to those of such indexes may be of limited use.

The information contained herein should be considered to be current only as of the date indicated, and we do not undertake any obligation to update the information contained herein in light of later circumstances or events. This publication may contain forward looking statements and projections that are based on the current beliefs and assumptions of Chilton Capital Management and on information currently available that we believe to be reasonable, however, such statements necessarily involve risks, uncertainties and assumptions, and prospective investors may not put undue reliance on any of these statements. This communication is provided for informational purposes only and does not constitute an offer or a solicitation to buy, hold, or sell an interest in any Chilton investment or any other security.

for more info on our strategy

go now →

for more info on our strategy

go now →

VIEW CHILTON'S LATEST

Media Features

go now →

Contact Us

READ THE LATEST

REIT Outlook

go now →

disclaimers

terms & conditions & FORM ADV

SITE CREDIT

Navigate

HOME

TEAM

REITS 101

Approach

OUTLOOKS

media

Contact

back to top

VISIT CHILTON CAPITAL MANAGEMENT

This property and any marketing on the property are provided by Chilton Capital Management, LLC and their affiliates (together, "Chilton"). Investment advisory services are provided by Chilton, an investment adviser registered with the SEC. Please be aware that registration with the SEC does not in any way constitute an endorsement by the SEC of an investment adviser’s skill or expertise. Further, registration does not imply or guarantee that a registered adviser has achieved a certain level of skill, competency, sophistication, expertise or training in providing advisory services to its advisory clients. Please consider your objectives before investing. A diversified portfolio does not ensure a profit or protect against a loss. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Investment outcomes, simulations, and projections are forward-looking statements and hypothetical in nature. Neither this website nor any of its contents shall constitute an offer, solicitation, or advice to buy or sell securities in any jurisdictions where Chilton is not registered. Any information provided prior to opening an advisory account is on the basis that it will not constitute investment advice and that we are not a fiduciary to any person by reason of providing such information. Any descriptions involving investment process, portfolio construction or characteristics, investment strategies, research methodology or analysis, statistical analysis, goals, risk management are preliminary, provided for illustration purposes only, and are not complete and will not apply in all situations. The content herein may be changed at any time in our discretion . Performance targets or objectives should not be relied upon as an indication of actual or projected future performance. Investment products and investments in securities are: NOT FDIC INSURED • NOT A DEPOSIT OR OTHER OBLIGATION OF,OR GUARANTEED BY A BANK • SUBJECT TO INVESTMENT RISKS, INCLUDING POSSIBLE LOSS OF THE PRINCIPAL AMOUNT INVESTED. Investing in securities involves risks, and there is always the potential of losing money when you invest in securities including possible loss of the principal amount invested. Before investing, consider your investment objectives and our fees and expenses. Our advisory services are designed to assist clients in achieving discrete financial goals. They are not intended to provide tax advice, nor financial planning with respect to every aspect of a client’s financial situation, and do not incorporate specific investments that clients hold elsewhere. Prospective and current clients should consult their own tax and legal advisers and financial planners. For more details, see links below to CRS (Part 3 of Form ADV) for natural person clients; Part 2A and 2B of Form ADV for all clients regarding important disclosures.